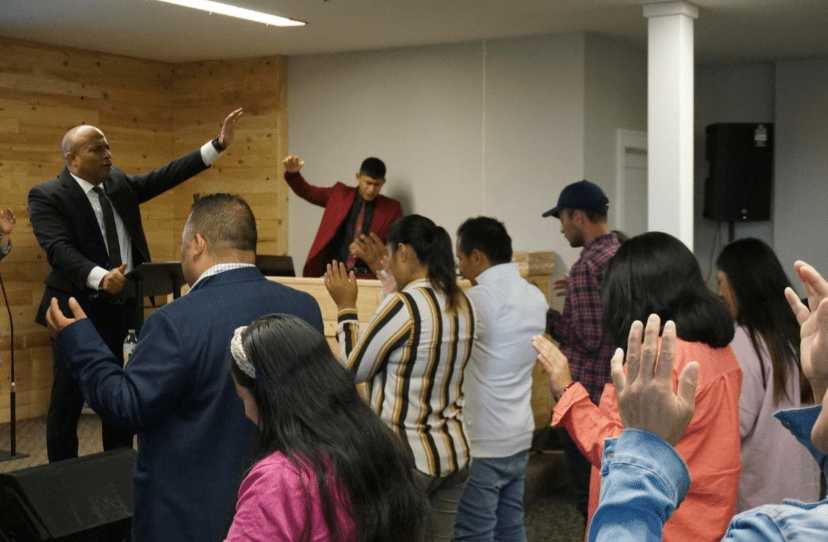

In Columbia Heights, Minnesota, the Rev. Gustavo Castillo passionately guided his expanding Pentecostal congregation through prayer, Scriptures, uplifting music, and heartfelt testimonials one Sunday afternoon.

However, this could soon come to a halt. A sudden procedural shift in how the federal government handles green card applications for foreign-born religious workers, alongside record numbers of illegal border crossings, is jeopardizing the ability for clergy like him to stay in the country.

“We were right on the brink of securing permanent residency, and suddenly, everything changed,” said Castillo, who was born in Colombia, as his wife cradled their 7-month-old son, born a U.S. citizen. “We’ve followed all the correct procedures; from here on, we trust that God will perform a miracle. We have no other choice.

Becoming permanent U.S. residents, a pathway that can eventually lead to citizenship involves immigrants applying for green cards. Typically, these applications are made through U.S. family members or employers. The availability of green cards is limited, determined annually by Congress and divided into categories based on the closeness of family relationships or the skills required for a job.”

Citizens from countries with disproportionately high numbers of migrants often find themselves in separate, and often longer, green card queues. Presently, the most delayed category involves the married Mexican children of U.S. citizens – only applications submitted before March 1998 are under processing. For religious leaders, the queue historically was short enough for them to secure a green card before their temporary work visas expired, according to attorneys.

However, this changed in March. The State Department revealed that for almost seven years, it had incorrectly placed tens of thousands of applications for neglected or abused minors from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador in the wrong line. These applicants would now be added to the religious leader queue. Since the mid-2010s, a growing number of youth from these countries have sought asylum after illegally entering the U.S.

This alteration implies that only applications filed before January 2019 are presently being processed. While it slightly advances the applications of Central American minors by a few months, it leaves clergy members with expiring visas, like Castillo, no choice but to leave their U.S. congregations behind.

Suddenly, these individuals, who are diligently following the rules, find themselves completely overwhelmed,” said Matthew Curtis, an immigration attorney based in New York City. His clients, including an Israeli rabbi and a South African music minister, are rapidly running out of time. “It’s like a bombshell hitting the system.”

Attorneys estimate that the queue has grown so extensive that the wait time is now at least a decade long, given that only 10,000 of these green cards can be issued annually. Curtis’s firm cautions potential clergy applicants that there’s no indication of when they might receive a green card. This uncertainty is likely to discourage religious organizations from hiring foreign workers at a time when they’re most needed. The demand for leaders of immigrant congregations who can speak languages other than English and understand various cultures is steadily rising

There’s a comfort in practicing your religion in your native tongue, with someone who understands your culture leading the Mass,” said Olga Rojas, the Archdiocese of Chicago’s senior counsel for immigration. The U.S. Catholic Church has relied on foreign priests to address a shortage of local vocations.

In a Chicago-area parish assisting this year’s influx of arrivals from the border, two Mexican religious sisters have initiated ministries for women in shelters, along with English classes, Rojas mentioned. She added that these sisters know they won’t receive green cards and anticipate the departure of other religious sisters and brothers, including teachers and principals. “That’s catastrophic.”

Members of religious orders bound by vows of poverty, such as Catholic nuns and Buddhist monks, are severely impacted. Most employment visa categories require employers to demonstrate payment of prevailing wages, but since these individuals receive no wages, they do not qualify.

Across all faith traditions, there are limited options for these workers to sustain their U.S.-based ministry, according to attorneys. At the very least, they would need to go abroad for a year before becoming eligible for another temporary religious worker visa. This process must be repeated, involving substantial fees, throughout the decade—or as long as their green card application remains pending

“A major concern is the lack of viable options if they have to leave. The church might find a replacement for the pastor, or it could shut down; the instability is too much,” said Calleigh McRaith, Castillo’s attorney in Minnesota.

Being in this uncertain situation is incredibly challenging for the affected religious workers, including Stephanie Reimer, a Canadian serving a nondenominational Christian youth missionary organization in Kansas City. Her visa is set to expire in January.

“I’ve done a lot of praying,” she said. “There are days when it feels overwhelming.”

Martin Valko, an immigration attorney in Dallas whose clients include imams and Methodist pastors, mentioned that many rely on their faith to stay hopeful.

However, realistic options are so limited that the American Immigration Lawyers Association, along with faith leaders such as Chicago’s Catholic cardinal and coalitions of evangelical pastors, have lobbied the Biden administration and Congress to address the issue. Potential administrative solutions could involve allowing religious workers to file for their green cards, enabling them to obtain temporary work authorization similar to those in other queues awaiting permanent residence.

The most effective and immediate solution, according to attorneys, would be for Congress to remove the vulnerable minors’ applications from this category. Despite being humanitarian cases, they constitute the vast majority of the queue shared with religious workers, said Lance Conklin, a Maryland attorney who co-chairs the lawyer association’s religious workers group.

“They shouldn’t be pitted against each other in competition for visas,” said Matthew Soerens, who leads the Evangelical Immigration Table, a national immigrant advocacy organization.

Back at the Iglesia Pentecostal Unida Latinoamericana, Castillo said he has ministered to families who survived treacherous journeys, including the perilous Darien Gap in Central America favored by smugglers, and individuals who entered through breaches in the border wall.

“Some of them are in a better migration situation than ourselves,” Castillo said. “But my call to minister to them is undaunted. I serve God. He will take charge of these affairs while I lead those he has entrusted to me.”

That’s why, even as they face the possibility of leaving the country when their visas expire in February, the Castillos are fundraising to purchase the building where they currently rent worship space. They also regularly drive 10 hours to South Dakota, where they’re establishing another church.

“In this work, we are constantly helping devastated migrant families,” Yarleny Castillo said. “And they need a space like this.”